System improvements could expedite benefits during pandemic

As thousands of New Jersey residents lose their jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many are turning to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to put food on the table.

New Jersey has taken steps to make it easier for people to receive SNAP, also known as food stamps. More flexibility in federal rules and improvements to state systems, however, would make it easier for people to access these critical benefits during a crisis.

This problem is made worse by the fact that, even in normal times, an estimated 300,000 of New Jersey’s poorest residents are missing out on this federal food assistance that reduces hunger and improves health, a new Hunger Free New Jersey report finds.

“We know people face hunger all year long,’’ said Adele LaTourette, director, Hunger Free New Jersey. “But the need for strong safety nets is amplified during a crisis like the coronavirus pandemic.

“We know the New Jersey Department of Human Services is working under very difficult circumstances and has taken strong steps to provide this assistance to the many new applicants,’’ LaTourette added. “We also commend the frontline county staff who are risking their health to respond during this crisis.’’

But, LaTourette said, this pandemic amplified some of the system’s challenges, which must be addressed to both deliver aid during a crisis and in normal times.

“More effective statewide systems would provide stronger resources for frontline staff to help our poorest residents and those suddenly in need when disaster strikes,’’ LaTourette noted.

The non-profit organization’s new report, Missed Dollars, Bare Cupboards, found that in 2018, New Jersey reached just 71 percent of very low-income residents through SNAP, leaving roughly 300,000 residents unserved. Participation varied widely among counties, ranging from a low of 27.8 percent in Hunterdon to a high of 84.5 percent in Hudson and 84.3 percent in Atlantic.

View county level data, all residents.

Senior citizens fared even worse. Only 56 percent of New Jersey’s low-income elderly received SNAP in 2018. Hunger is particularly detrimental for seniors, who are more likely to suffer health problems when they lack enough healthy food to eat, LaTourette noted. Again, county participation varied widely.

View county-level data for senior citizens.

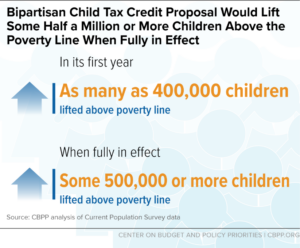

“SNAP is the nation’s first line of defense against hunger,’’ LaTourette said. “It is well-documented that SNAP lifts people out of poverty and improves their health and well-being.’’

In addition to reducing hunger, reaching all low-income residents would mean more federal dollars flowing into New Jersey communities. The report estimates the state would claim an additional $155.5 million annually to feed struggling residents, if all low-income residents were reached.

To make it easier for people to apply for SNAP during the pandemic, the state has waived several rules, including eliminating the interview requirement and allowing applications to be submitted without a hard copy signature. Applications can also be provided to county boards of social services by phone.

Despite these measures, inadequate statewide outreach, cumbersome online and paper applications and certain state rules are making it difficult to quickly provide SNAP to the thousands of suddenly unemployed residents.

Statewide, just two non-profit organizations – Fulfill and Community Food Bank of New Jersey – receive federal dollars to conduct outreach to residents in need who are not receiving SNAP. Seven of New Jersey’s 21 counties have no government-contracted SNAP outreach workers, the report found.

Typically, outreach staff sit down with applicants and help them complete the process. Now, all outreach work is being conducted over the phone. This limits staff’s ability to guide applicants through the complicated and cumbersome paper and online applications. State rules prevent outreach staff from filing phone applications on behalf of their clients.

Challenges in the online application system are also exacerbating the problem. According to Hunger Free New Jersey’s report, New Jersey’s online application system is “difficult to use, with interfaces that are cumbersome and that instruct applicants to use outdated software.’’

The USDA denied New Jersey’s request to expedite all applications. This would have allowed the state agency to approve applications without income verification.

Instead, applicants must either mail that documentation or leave it in the county welfare office’s “drop box’’ because the online system does not allow applicants to upload supporting documentation.

“With county offices closed to the public, the ability to complete online applications with documentation would enable us to get SNAP to people much faster during the pandemic,’’ LaTourette said.

To address these issues, DHS should immediately:

- Simplify both the paper and online application.

- Pursue avenues to allow state-contracted outreach workers to submit applications over the phone.

- Provide a secure, electronic method for applicants to provide documentation to verify income.

- Post clear instructions for the various ways people can apply for SNAP on njsnap.gov.

“Emergency food providers are struggling to keep up with the growing demand,’’ LaTourette said. “SNAP is essential to meet the need. While the state and counties are working hard to address the emergent need, we need to take steps that can deliver SNAP more quickly to people during this time.

“We also need to work on long-term solutions to strengthen this system so we are better prepared in the future,’’ she added.

In 2019, NJ SNAP helped an average of 682,633 residents afford food, including more than 316,000 children and contributed about $1 billion to New Jersey communities. Most recipients spend their monthly benefits in local supermarkets, bodegas and other retail outlets that accept SNAP.